Tim Robertson, Chief Executive of the Koestler Trust talks about The Ingram Collection’s purchases from The Koestler Trust and the importance of the work being done by The Koestler Trust.

Prison art: inside or out?

I am absolutely delighted that Chris Ingram has added some Koestler artworks to his collection. It is a sure and exciting sign that Britain’s unique tradition of prison art is gaining a place in the front rank of cultural taste. And I see compelling reasons for more collectors to start looking for creative talent in that most surprising of contexts – the criminal justice system.

The Koestler Trust makes Britain the only country in the world with an arts awards scheme open to all its offenders and a national programme of exhibitions to bring those arts to the public. The Trust was founded in 1962 by the writer Arthur Koestler, who was a political prisoner in the Spanish Civil War and World War Two (though he did not leave an endowment when he died in 1983). The annual Koestler Awards now generate 8,000 entries in 60 artforms from over 300 prisons and probation services across the UK, with judges including Jeremy Deller, Sarah Lucas, Grayson Perry and Bob & Roberta Smith. Koestler Exhibitions attract 40,000 visitors a year to a national show at London’s Southbank Centre, and regional shows at such venues as BALTIC in Gateshead, Tramway in Glasgow and the Millennium Centre in Cardiff.

In the contemporary art world, prison art is generally included under the umbrella of “outsider art” – created by non-professional artists with little or no academic training. Many Koestler Awards entries are indeed in classic “outsider” style – naive, technically simple or obsessively repetitive images generated without any conscious agenda, by artists who can often give no verbal explanation for their artistic choices. The very difference of this work from postmodern conceptualism is exactly its appeal to the art world: it shines out as an unpretentious breath of fresh air.

But this is only part of the picture. Many offender-artists achieve high levels of technical proficiency – not least when pursuing traditional prison crafts like matchstick modelling, soap carving and bread-sculpting. This is not so much “outsider art” as “folk art” (as revived in this summer’s Tate Britain exhibition) – a reminder that professionally-produced art is merely the visible tip of the iceberg of creativity in our society. The bulk of arts activity takes place through amateur pursuit in people’s homes and communities. And prison art offers a particular insight into this cultural undercurrent – because prison provides the stability, time and basic resources for artistic achievement by many individuals whose lives are on the outside are too stressful and chaotic for them to put pen to paper. Prison art opens up a unique channel both for individuals in extremis to express themselves, and for society at large to gain insight into the experience of those on its margins.

Moreover, many offenders consciously and skilfully use art to capture and convey their worldview – including the causes of crime, the process of criminal justice, the reality of imprisonment, the expression of defiance or remorse, and the prospects of personal change and a better future. For prisoners, these are not just complex social issues, but urgent questions of lived experience – and it is this urgency that perhaps above all makes prison art so fascinating in its ambivalence and so gripping in its emotion.

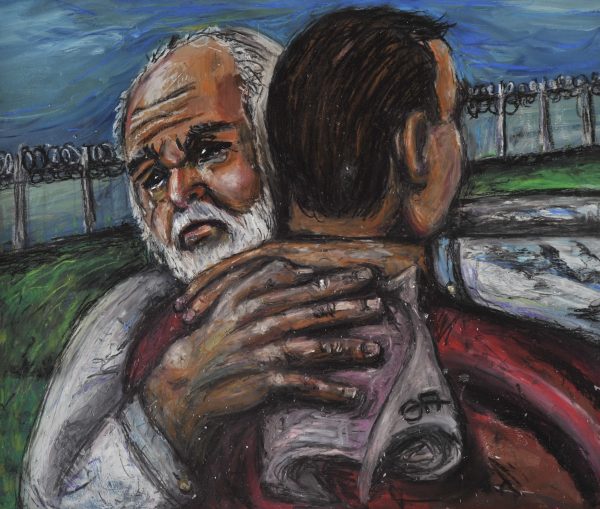

These themes are epitomised in the two works selected by Chris Ingram. In the painting “The Prodigal Returns” (from HMP Whatton in Nottinghamshire), the tearful embrace of a father and son by a prison wall may be either a grateful memory, an admirable goal or a hopeless fantasy, but is carried by the sheer directness of its yearning. And yearning is even more vivid in the painted poem “Back to the Sea” (from HMP Stafford):

Show me the sea, the shining sea

and let me breathe it in

bit by salty bit.

I’ll close my arms around the waves

and wash my soul in it.

Here the poignancy of the poet’s imprisonment – longing to go “back” to the sea and for his sins to be expunged – is exactly what frees him to be so rapturously romantic in evoking the ocean. The unresolvable drama of entrapment and release, of aspiration and frustration, is fundamental to generating creativity in all forms and contexts, and this pervasive cultural driver is explored nowhere more vividly than in the art of prisoners.

For the most accomplished offender-artists, perhaps the greatest value in exhibiting and selling their work is that it can challenge social stereotypes about offenders – can demonstrate their humanity, talent and potential. For the art world, perhaps the greatest value of offender art is that it can challenge social stereotypes about art – where art comes from, how its quality can be judged, and how it may relate to some of life’s most profound questions of possibility and truth.

Tim Robertson

Chief Executive, Koestler Trust

Catching Dreams: Art from the 2014 Koestler Awards, Curated and hosted by ex-offenders

Royal Festival Hall, South Bank

24 September – 30 November 2014

Daily 10am – 10pm, admission free