The Lightbox gallery and museum is home to The Ingram Collection – an extraordinary collection of contemporary works, many of which will star in the gallery’s latest major exhibition The Colourful Lives of Artists. The show will explore the often controversial and complicated lives of sculptors and painters, exposing their private lives, their personal relationships and the inspiration behind their artistic practice.

Little of that intrusive light, however, is cast on Chris Ingram the man behind the collection – a Woking boy whose business and philanthropy have injected new life into some of the town’s ailing quarters.

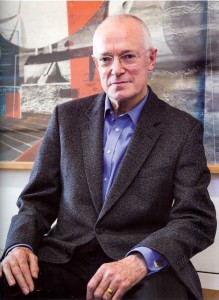

I meet him in a hotel cafe a few hundred yards from the celebrated gallery that scooped the coveted The Art Fund prize in 2008. His contagious enthusiasm betrays his 68 years – throwing his weight behind an abundance of projects, from the arts, sports and entrepreneurial pursuits, Ingram spurns retirement, ruling little distinction between his work and leisure.

“It’s not me. I suppose I’m just somebody who needs projects,” he laughs, sipping his black coffee. “I’ve been a boss since I was 27. Most people retire because they’re fed up with somebody telling them what to do, the insecurity they might be fired, or working a very boring job in a factory. One understands all those reasons. But I’ve never had a boring job.”

Ingram was born in Weybridge, the son of a policeman. Contingent on his father’s work, the family moved frequently within Surrey. At the age of 11, they settled in Woking where the young Chris attended grammar school.

At 16, unclear of which direction to take, Chris abandoned study and began the hunt for work.

“I left halfway through sixth form. I had always found it very difficult academically,” he shrugs. “My father was raging at me that I had no chance because I didn’t have O Level maths.”

“All those years ago you were looking for security and there was nothing more secure than banking or insurance. Heaven help us, thank God I didn’t get O Level maths!” he laughs, spreading his hands wide. “But my father regarded me as a failure.”

One area open to the school leaver was advertising. Acting on his sister’s advice, he took a job as a messenger boy at a London ad agency. Between errands, the youngster independently took an interest in media research. He was soon offered an assistant role, yielding further opportunities.

After a decade of intensive work, moving between departments and agencies, Ingram became a board member at the tender age of 26. In 1970 he launched his own campaign planning firm, Chris Ingram Associates.

Acknowledged as the godfather of the modem media agency, he sold the firm in 2001 for a whopping £435 million.

“I suppose, largely, I am a self-made-man,” he says, tentatively. “I can’t pretend I was in rags and no shoes as it were, because that wouldn’t be fair at all. But in terms of starting at the bottom and working my way up, I guess that’s true – without any connections at all, or financial benefit.”

A solemn moment passes. “I had certain advantages. But having a father who thought I was a failure, funnily enough, drove me on hugely. For some people that is very damaging, because they lose all confidence. Alternatively, you’ll say to yourself, how will I show the old devil?”

With over 40 years’ experience in the industry behind him, and a huge personal fortune at his disposal, Ingram was able to devote his energies to wider interests.

Through his charitable fund, The Ingram Trust, the media comms magnate has aided causes as diverse as the housing charity, Shelter, and the World Wide Fund for Nature.

From 2000, the lifetime soccer fan made anonymous loans to Woking Football Club, which had long tiptoed near the precipice of financial collapse. In exchange, Ingram received regular budget updates. His suspicions were roused when the updates abruptly stopped.

“When I finally insisted on getting the information, the club was in a horrendous state,” he says, shaking his head. “There was no one on the board with any business experience.

“This is often the problem with football clubs. There are tens of thousands in this country, all with their dreams. But their brains get scrambled by the excitement of potential promotion and the fear of relegation. Those are the key things in the sport.”

Ingram had never intended to purchase a football club. But with the successful sale of the firm and the agony of seeing his home team decay, he relented and bought the club in 2002.

“Some smart people go into the sport, but those who do almost inevitably end up parking their brains in a plastic bag at the side of a boardroom when they walk in and then make all the mistakes they swore they never would!

“There’s so much passion, and people give the most amazing amount of their time, but there’s clearly far too much emotion in these clubs.”

Today, Ingram has renounced his chairmanship, and is now effectively the club’s landlord – and a benevolent one at that. Rent for the Kingfield grounds amounts to a mere £1 a year.

“It’s a tribal thing, football. I’ve been a supporter since the age of 11, so I’m not going to turn around and find some way of lining my pockets at the expense of the club.”

To own your local team is surely every boy’s dream. But art collecting is a different kettle of paintbrushes altogether. What sparked this interest?

“There were two light bulb moments,” he reflects. “One was when I’d just become a director at the agency Kingsley, Manton and Palmer in my mid-20s. In those days of lavish entertaining, one of the publishing companies took 30 to 50 media directors on a jaunt to Leningrad and Helsinki. The Iron Curtain was firmly in place then, so the trip was very, very unusual.

“We were inevitably shepherded around everywhere, and we went to the Hermitage Museum. I didn’t know what the hell it was – that it was one of the most famous galleries and art museums in the world. And at one stage I saw the most stunning collection of Impressionists, and that sort of knocked my socks off.”

Ingram’s second light bulb moment came at a pre-auction viewing in Sotheby’s. Struck by the relatively modest price of some British works that caught his eye, Ingram learned he could build a sizeable collection, which had the potential to rocket in value.

“I soon found I had so much art work about that I had to start putting some in storage. So when I was asked to put money into The Lightbox, but couldn’t because I had just bought the club, I loaned my collection to the gallery instead. It’s just wasted on a sad old git like me otherwise!”

“A lot of people ask me if I am collecting art to make money or because I like it,” he says. “Well, it’s a bit of both. I just go in with my usual mixture of enthusiasm and obsessiveness.”

Article courtesy of The Woking Lifestyle Magazine