The Ingram Collection of Modern British Art celebrates the work created by British artists of the 20th century.

The collection currently holds 443 works by 151 different artists – a rich catalogue of considerable depth and range.

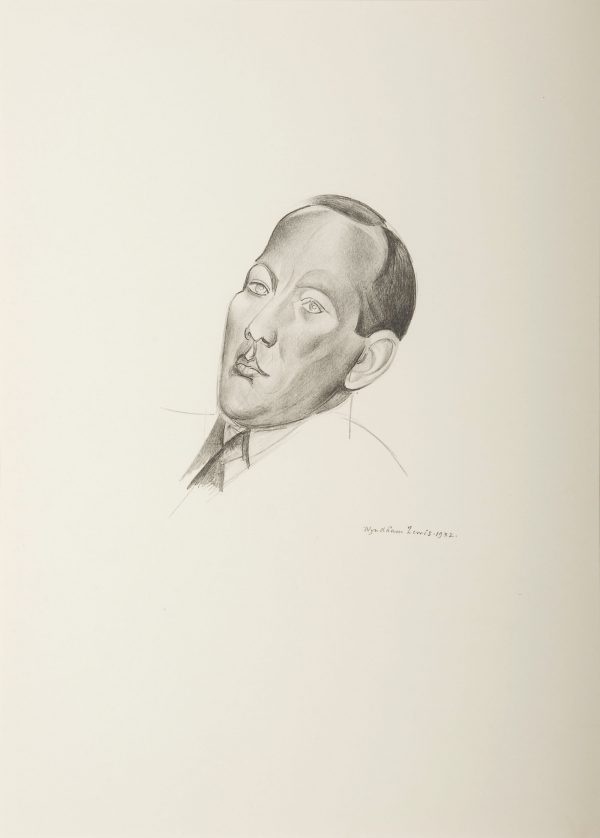

Wyndham Lewis, Noel Coward

Concentrating on British painting, drawing and sculpture of the twentieth century, with particular reference to the post-war period, it presents both a survey of a century of change and an opportunity to study in depth the work of many of that century’s leading artistic figures.

Some of the earlier works in the collection are on paper and may not immediately command the attention of larger scale oils and bronzes. This would be to overlook a fine, introspective study of Lady Ottoline Morrell by Henry Lamb or Wyndham Lewis’s stylish portrayal of a young Noel Coward. Both portraits represent the art of two artists from a period which threw up a hugely talented generation. That much of that talent fell on Flanders Fields is marked by a small bronze by Henri Gaudier-Brzeska who died soon after the beginning of the First World War. Despite his incredibly brief career Gaudier-Brezska produced outstanding work in a variety of media and, with his contemporary Jacob Epstein, laid the foundations for much of the development of twentieth century British sculpture.

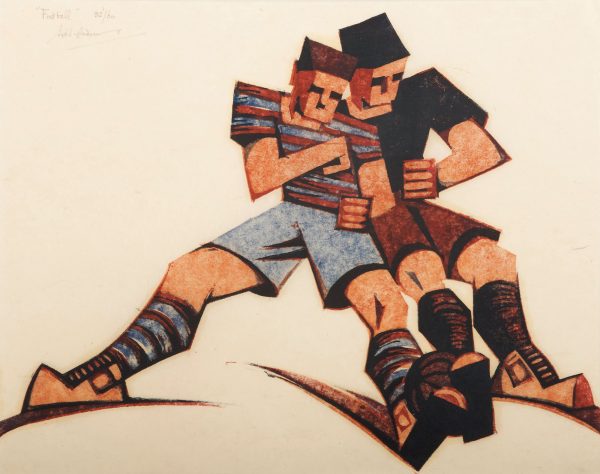

Sybil Andrews, Football, 1937

By the 1930s, influences from Modernist Europe had infiltrated the British art scene, influences which were to have resounding and long lasting effects on its future. Earlier in the century there had been a brief, but robust, reaction to the artistic revolution brought about by the art of Cezanne, Matisse and Picasso but it had been short-lived and abruptly curtailed by the outbreak of war. Now, the lessons of Cubism and Futurism were incorporated into the visual language and were particularly effective in the work of printmakers in the 1930s. Examples by two of the leading

exponents of the art, Cyril Power and Sybil Andrews, are in the collection. Surrealism exploded – almost literally in the case of Salvador Dali’s appearance in London – during the decade, and its flights of fantasy touched the work of many British artists, work which, however, often retained a characteristic restraint. One artist who responded to the idiosyncratic imagery of the Surrealists was Edward Burra and it underpinned much of his work for the rest of his life. The traditions of portraiture and landscape were kept alive by artists like Dod Proctor and Laura Knight, both of whom worked in Cornwall, a county which has attracted artistic communities since the late nineteenth century, and which would be the inspiration for some of the most significant British art of the twentieth century.The years between the First and Second World Wars saw an understandable retreat into the order and calm of the natural world and a desire to interpret this in a series of responses. C.R.W. Nevinson’s La Corniche portrays a scene a million miles from the battle fields of Northern France which he had recorded only a few years previously. Another artist who had served in the trenches was John Nash and his return to the peace of Buckinghamshire is captured in a watercolour of Whiteleaf in that county. Such responses ensured that landscape was a favoured subject of many artists and watercolour was often the chosen medium. Works on paper by David Jones, Eric Gill and Eric Ravilious are included in the collection.

Henry Moore, OM, CH, Seated Girl, 1947-48

It is perhaps in the sculptures by Leon Underwood that we can see a very direct reaction to the lessons of Modernism: in the sinuous stylisation of Atalanta or the primitive power of Birth of Eve. Ben Nicholson, Henry Moore and Barabara Hepworth (all represented in the collection) were all involved at the time in creating a new voice for painting and sculpture which would be heard loud and clear over successive decades.

The outbreak of the Second World War involved artists once more as official recorders of the conflict. This conflict did not produce such visceral imagery as its predecessor, which is only to be expected from a very different theatre of war, but there were notable exceptions. David Bomberg’s Bomb Store, for which there is a large oil study in the collection, was the artist’s only major war commission and he approached it with the power and intensity which informed so much of his art.

Works in the collection dating from the half century following the war years clearly reflect the developments and advances in British art and more particularly sculpture. With outstanding bodies of work by individual painters and sculptors, it would be possible to extrapolate ‘mini one person shows’ of several leading figures in both disciplines. William Roberts, ex-Vorticist and later shrewd observer of the pleasures and pastimes of the British, is represented by no less than eighteen oils and works on paper covering much of his long career. Paintings by the next generation of artists to be drawn by the lure of St Ives in the 1950s, include those by Patrick Heron, Terry Frost, Bryan Wynter, Peter Lanyon, and Roger Hilton. This was also the decade when the everyday became the subject for artists concerned with capturing the bleak, mundane aspects of post-war Britain, artists such as John Bratby and Ruskin Spear. The swinging sixties changed all that with the advent of Pop Art which was fuelled by the increasingly informative – or intrusive – power of the mass media. Some artists, like Tristram Hillier, worked in the same style which had characterised their art much earlier in the century. The Scottish contingent – a force in the advancement of visual art throughout the century – continued to produce artists of strength and originality from Anne Redpath to John Bellany.

Patrick Heron, Storm at St Ives, 1952

Whilst painting in the 1950s often reflected the austerity of the time through depictions of the familiar, sculptors like Kenneth Armitage, Lynn Chadwick and Reg Butler responded to the climate of fear which surrounded the country during the Cold War with the threat of nuclear warfare. Working primarily in bronze, their mysterious, edgy figures embody the apprehensions and sense of isolation which characterised the period. The critic Herbert Read described the art of the group as ‘new images [belonging] to the iconography of despair … images of flight’. Another artist well represented in the collection is Eduardo Paolozzi who was working at something of a tangent and making as much art in two dimensions as three. He went on to establish a distinctive sculptural style incorporating a love of Surrealism and mass media imagery expressed in mechanistic forms. These forms often assumed a robot-like identity which in turn mirrored the psychological alienation of the work of his peers. By the 1960s the art of one of the most talented of the next generation of sculptors came to maturity. Elisabeth Frink had entered the famous Monument for the Unknown Political Prisoner competition (held in 1953 and won by Reg Butler) when she was still a student and gained a distinction; she went on to produce her most iconic work over the next forty years. Of the considerable holdings in the collection, both in bronze and on paper, perhaps Goggle Head or In Memoriam III best embody that sense of power touched with the sinister which characterises so much of her art.

Dame Elisabeth Frink RA, Eagle (Lectern), 1962

Sir Anthony Caro, RA, Flageolet (Concerto Series), 1999

That generation of older artists who had enthusiastically embraced Modernism in the 1930s, namely Moore, Nicholson and Hepworth, were now the leading players in post-war abstraction. Henry Moore’s expressive war time shelter drawings were translated into monumental sculpted figures which also referenced his direct engagement with the natural world. Seated Girl of the late 1940s both reflects the pre-war work and anticipates that to come. Barbara Hepworth’s Sculpture with Colour and String – cast in 1961 – shows how comprehensively she had absorbed the language of European Modernism and became its leading exponent in Britain. From Jacob Epstein and Gaudier-Brzeska the art of sculpture had evolved and developed in a remarkable trajectory, whilst remaining primarily plinth-based; it took an engineer to take it off… After his Cambridge training and Naval war service, Anthony Caro worked as an assistant to Henry Moore in the early 1950s, but it was the work of the American sculptor David Smith which most influenced his mature style. Using metal, iron and steel Caro literally forged a new language for sculpture. Redoubt (one of three Caros in the collection) although small in scale, exemplifies Caro’s use of materials and assured handling of spatial composition.

With thanks to Anne Goodchild.