Elisabeth Frink was born in 1930. Her early childhood was an idyll (she had her own pony from the age of 3), but later it was also overshadowed by the Second World War. The Suffolk countryside was ideal territory for the air bases of the war, and she spoke later of the impression the aircraft and their pilots made on her. She cited this wartime experience as one of several sources of her imagery of birds and birdmen. She said that seeing planes crashing into fields (‘broken-winged creatures’), around the airfield near her grandparents’ house in Thurlow, Suffolk, had a lifelong impact on her. She was left with recurring dreams and said later in life: “I’ve had this flight dream from the time I was very young. It’s to do with birds flying, planes crashing – big monstrous things flying, sometimes with a man in them”.

After the War, her aesthetic sensibility was developed by a long trip to Northern Italy in the late 1940s. It took place at a time when most British civilians were still unable to travel, and her direct encounters with the art treasures of Venice, particularly the equestrian statues, excited her imagination and were to stay with her. She returned from Italy determined to go to art school and study painting. Her parents let her go even though she was only 16.

She first studied at Guildford School of Art, and then Chelsea. While a student she discovered that she liked to sculpt, mainly in plaster. By making a framework and then using fluid plaster and incorporating bits of wood, newspaper and even fragments of discarded dried-up plaster, she could quickly build up the form that she was working towards. At Chelsea she was taught by the sculptor Bernard Meadows who had also started to model in plaster. The emphasis on modelling is also found in other sculptors who studied at the Chelsea School of Art around 1950, such as Robert Clatworthy.

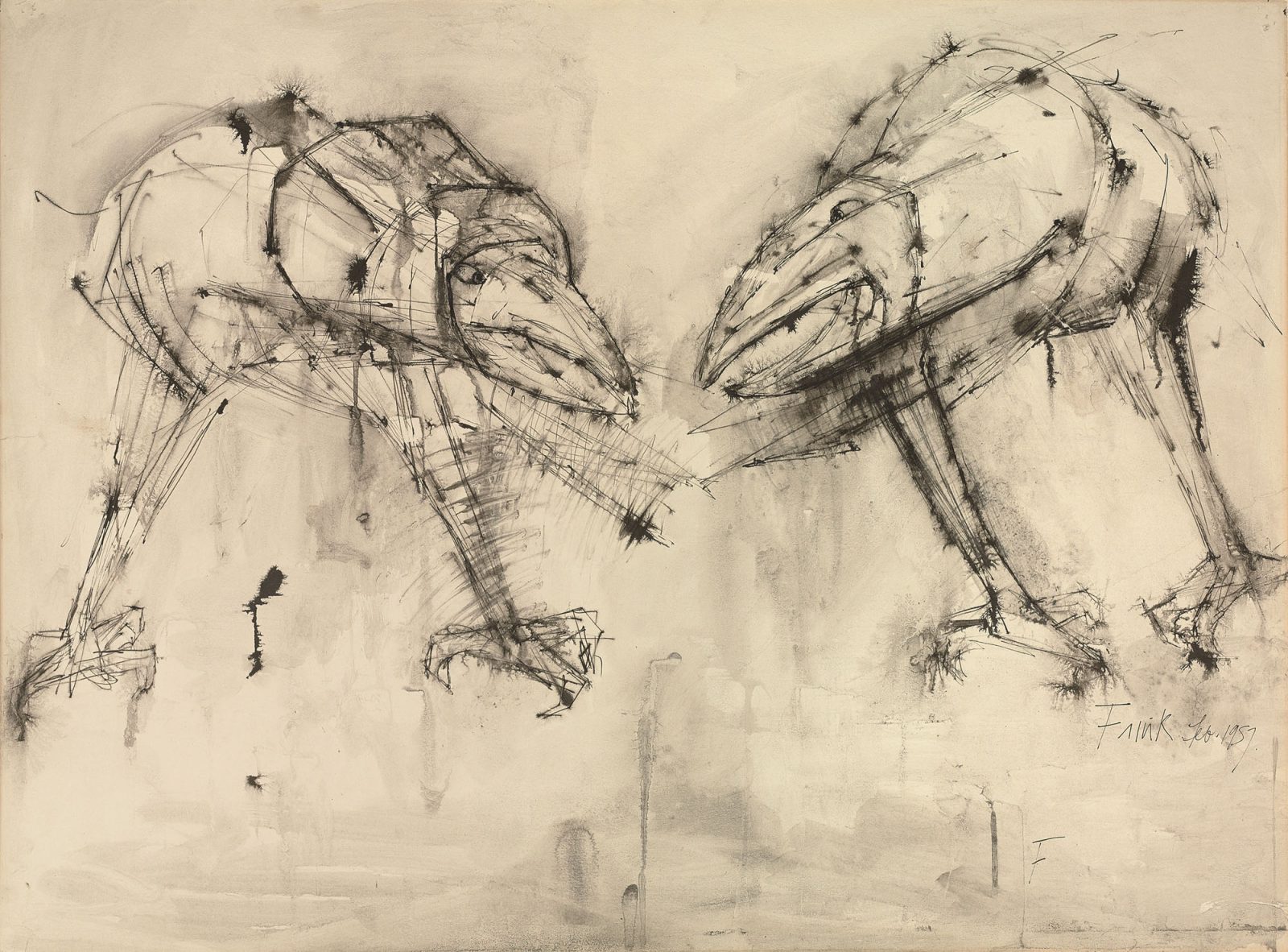

Frink received incredible early success and acclaim. She was still an art student at Chelsea, and only 22 years old, when the Tate bought ‘Bird’, in the early 1950s, from an exhibition at the Beaux Art Gallery in London. Her work of this time – expressionistic with flayed, violent tense forms – led to her being closely associated with the ‘Geometry of Fear’ sculptors. These were a group of men, older than Frink, such as Lynn Chadwick and Reg Butler, whose work at the 1952 Venice Biennale was described as “the most vital, the most brilliant and the most promising of the whole Biennale”.

It has been said that Frink’s early birds and birdmen are very much creatures of their time. She did understand that their aptness to the historical moment had undoubtedly played a role in winning her early recognition.

Birds were a common preoccupation among her contemporaries in the 1950s. Frink said later that they were “really vehicles for strong feelings of pain, tension, aggression and predatoriness”.

There were a number of themes that Frink constantly reverted to – her preference for the male rather than the female, for example, and her tendency to work in a series. This tendency, in turn, she linked to her search for archetypal images.

Her ‘Goggle Heads’ for example belong to a series of Head sculptures from the 1960s which stem from a questioning and uncompromising preoccupation with masculine power that was central to Frink’s work. These works are quite unexpected to those familiar only with the softer imagery of her dogs and rolling horses.

Frink talked at the time about the fact that these Goggle Heads were modelled on the Moroccan General and Minister of the Interior, Mohammed Oufkir. She had seen a photograph of him in the newspaper, wearing sunglasses, and said that Oufkir’s face in sunglasses had created for her an exceedingly sinister impression, which she had taken as the starting point for the series. Oufkir regularly featured in the media during the period when Frink lived in France, since he was accused of ordering the assassination of the exiled politician Ben Barka.

In her later heads of the late 1970s and 1980s, such as In Memoriam, the eyes are visible, but closed. These are larger than life-sized heads and are made with the deliberate goal of empathy. While the Goggle Heads (and earlier Solider Heads) were instances of highly personal imagery, these monumental heads call to mind the tradition of portrayals of Christian martyrs.

Although Frink linked these heads in interviews with the aims of organisations like Amnesty International, she stressed that it was suffering itself that really interested her, regardless of its time in history. Her son, Lin Jammet, wrote of her work: “The aggressor is a constant theme in her repertoire, but with the bad comes the good. This is reflected in her portrayals of the vulnerable, the faithful and the courageous, human and animal forms striving for a peaceful and normal existence”.

Chris Ingram is a great supporter of the work of Elisabeth Frink and has said that one of the reasons he is so enamoured of her work is her ability to investigate different styles and materials – the rolling horses, sitting dogs and other animals contrast with the more searching, questioning aspects of her work, such as the Goggle Heads. Her ability as a draughtsman is also hugely important, and the Ingram Collection contains many of her powerful drawings.

For a full list of works by Frink held by The Ingram Collection, click here.